Introduction¶

Connor Gilroy

Department of Sociology

University of Washington

This project analyzes general public discourse in English about “community” using the computational text analysis method of word embeddings.

Community is a concept that social actors invoke in heterogeneous ways to a variety of ends. I find those varied uses interesting, and I suspect there’s some systematic structure underlying the variation. When protestors adopt “invest in community” as a core demand of their movement, what they mean is somehow fundamentally different from when a company adopts “give people the power to build community” as its mission The intrinsic flexibility and ambiguity of the word may be part of its power, but what’s different, and what’s common, is part of the puzzle.

At their core, all text-as-data approaches translate language into numbers. Word embeddings are a dense representation of text in a multidimensional vector space; that’s the key difference from the document-term matrices that feed into more familiar approaches like topic modeling. That dense vector representation enables different kinds of analyses – not necessarily better, just different.

NLP researchers have used embeddings for linguistic tasks like analogy and similarity for several years, and they’ve begun to develop more complex approaches like contextual and sentence-level embeddings. Meanwhile, social scientists are still sorting out how ordinary word-level embeddings might be useful to us. In sociology, cultural sociologists have led the way. Kozlowski et al (2019) published “The Geometry of Culture” in ASR, analyzing historical change in different dimensions of social class. In a series of methodological papers, Stoltz and Taylor (2019, 2020) have translated and extended an approach for measuring document similarities to measure concept engagement in texts. Arseniev-Koehler and Foster (2020) have developed a theory of bias and cultural learning. At the same time, political scientists (Rheault and Cochrane 2020, Rodriguez and Spirling 2020) have begun to apply embeddings models to legislative proceedings and political speeches.

These pages are a prototype for ongoing work. My intention is to develop this work into the first empirical chapter of my dissertation, and eventually into a publishable paper. My preliminary goal here isn’t to answer any particular empirical research question about community; it’s to implement and understand methods so I can determine which ones are most relevant for my substantive research interests. To that end, I’ve read the methods and code for some of the papers I described above, assessed their commonalities and differences, and implemented examples for what I see as common techniques in this new field.

In the following pages, I’ve grouped those techniques into four notebooks based on the distinct aims they accomplish:

Word similarity: The most straighforward application of embeddings is to measure the similarity between individual words. I compare and contrast two pretrained, widely-available sets of embeddings in terms of which words they highlight as most similar to the word “community”, and visualize those nearest neighbors to “community” with PCA. Despite the differences I uncover, the two sets of embeddings I examine ultimately show a moderately strong correlation in terms of how similar other words are to the word “community.”

Document similarity: Word-level embeddings can be used for comparisons beyond individual words, at the scale of entire texts. An approach for using word embeddings to produce a document-level measure of similarity is Word Mover’s Distance, or the related Concept Mover’s Distance. I show that this measure has reasonable face validity when ranking Wikipedia articles in terms of how related they are to the concept of “community.”

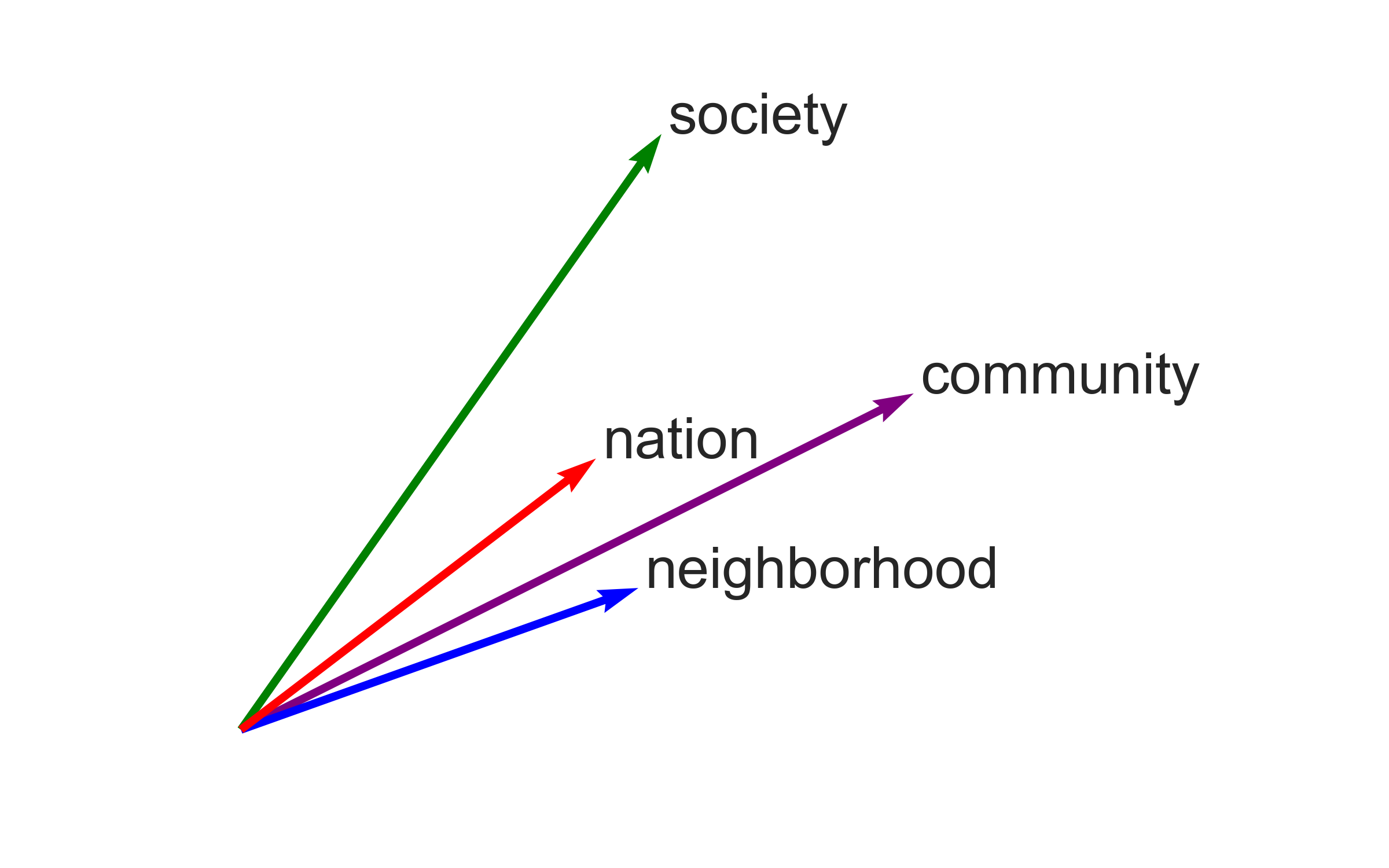

Binary axes: Word embeddings can be algebraically composed to represent binary concepts. I construct one binary dimension that differentiates “community” from the closely-related word “society”, and another that distinguishes words that are more “local” from those that are more “global”. I choose words similar to both “community” and “society” to evaluate against these dimensions, and I generally find that the results are intuitively reasonable.

Historical change: Comparing sets of historical embeddings is a way to examine how much a word’s meaning shifts or remains stable over time. I show that “community” has been relatively but not completely stable over the 20th century. Some other words have grown more similar to community as their own meanings have shifted. I use the notion of “gay community” as an illustrative example.

Of course, these separate techniques can be, and have been, combined in various ways. I don’t doubt that social scientists will continue to push the applications of word embeddings even further, and to translate, interrogate, and import the innovations coming out of NLP research. I close with a discussion outlining how I hope to contribute to this collective endeavor as I continue to develop this project.